This is a post about the generalization of the concept of global symmetries. This area has been a very active area of research for the last 8 years or so. A basic understanding of global symmetries unitary operators (acting on quantum states and operators) and local operators is required to read this post. This topic may look esoteric but it has applications in well known theories of physics, including the standard model.

In quantum mechanics, if we have a global symmetry, it acts on the states as unitary operators. These operators must be unitary to conserve the total probability equal to 1. The state of a system is defined at a particular time; thus, the unitary operator acting on this state may also depend on time.

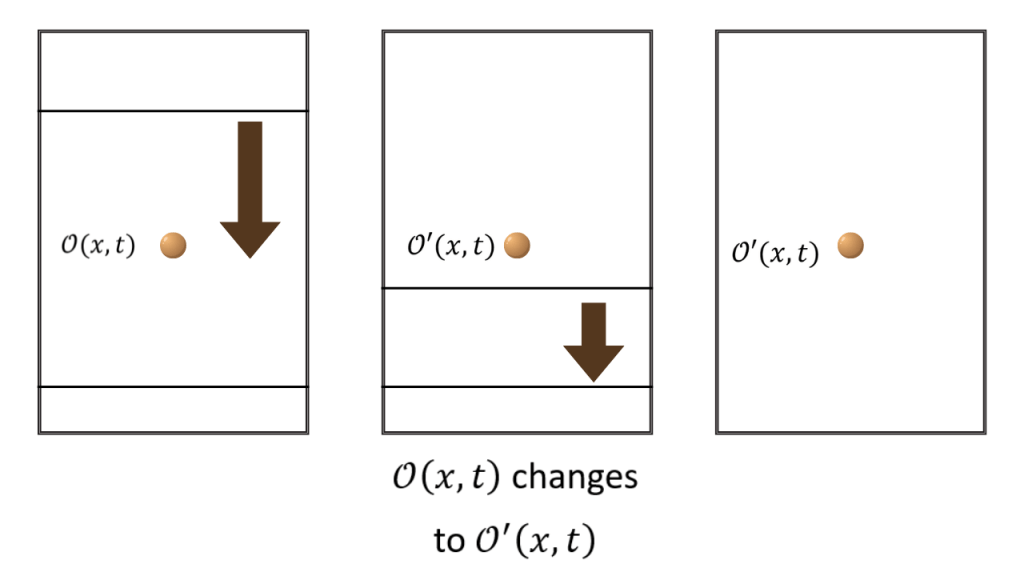

Now, if the system evolves with time, then the unitary operator also evolves with time. If we want U(t) to represent a symmetry, then it should be independent of time. In addition, if we have some local operator, it also changes under this symmetry.

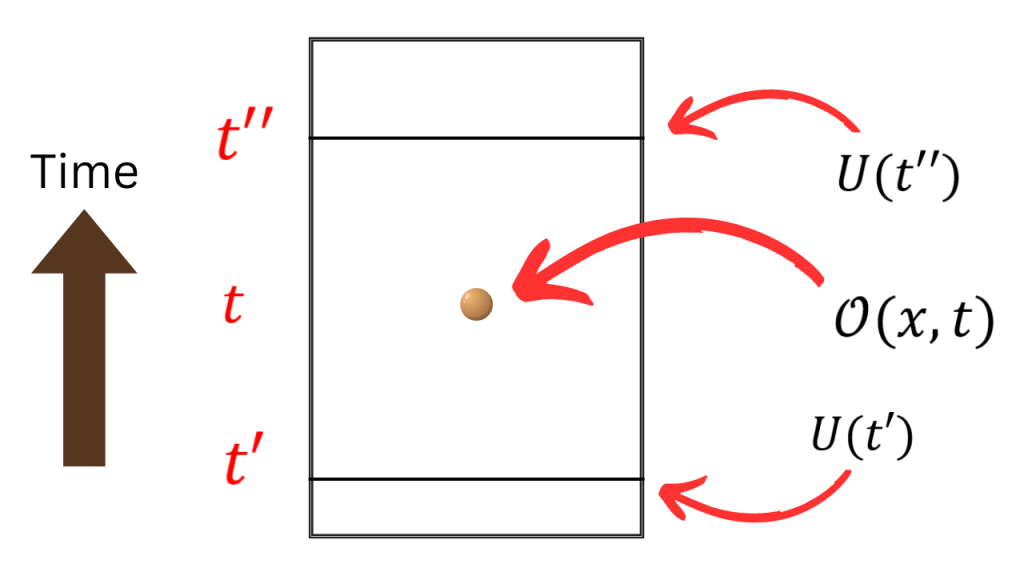

Let’s recast the story of the action of the unitary operator on the local operator in another way. Let the local operator be some time t and take two unitary operators at times t’ and t” such that t is between t’ and t”.

We see that we can’t make U(t”) meet U(t’) without going through the local operator. Now, we define the action of U(t) on the local operator by making U(t”) go through the local operator and then assuming that when U(t”) meets U(t’), they annihilate each other. This is because U(t’) has a reverse orientation relative to U(t”) and when they combine, U(t’) can be thought of as the inverse of U(t”) when it reaches the time t’. I will justify this assumption later.

Why could we move the operator U(t”) to U(t’)? It is because we saw that U(t”)=U(t’) for different times t” and t’. So, the scenario described above doesn’t change unless U(t”) passes through the local operator.

When a system has properties that don’t change under continuous deformations, we call such properties topological properties. The property U(t”)=U(t’) can be used to call U(t) as topological operators. We will now generalize this scenario.

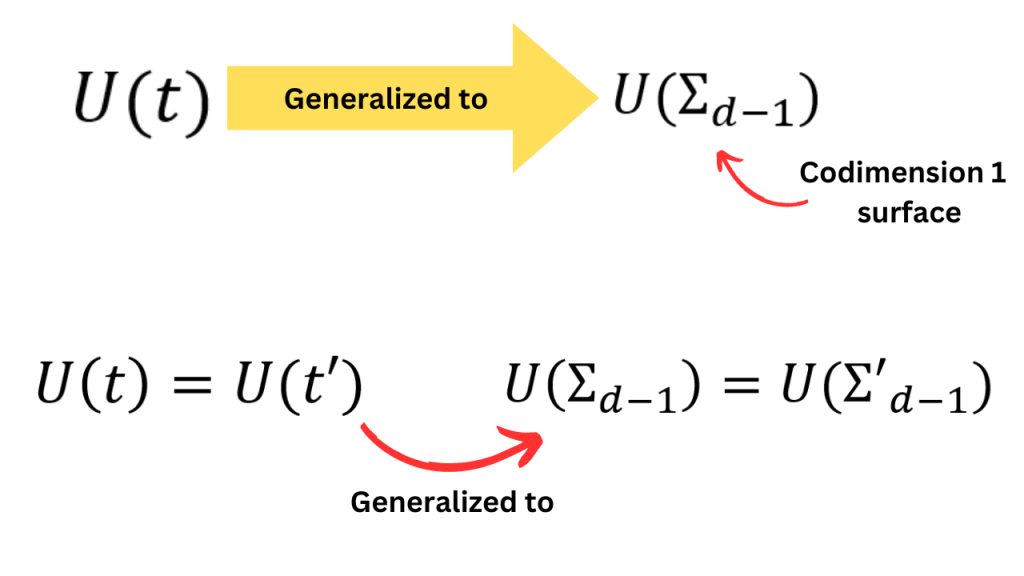

In the previous scenario, we associated a unitary operator with a time slice. If the dimension of spacetime is d, then the dimension of a time slice is d-1. Such a surface is called a codimension 1 surface (i.e. a surface of 1 dimension less than the total space). A surface of d-m dimensions will be called a codimension m surface.

Now, in relativity, a time slice doesn’t have a privileged position and thus, we can generalize the previous scenario to arbitrary codimension 1 surfaces (i.e. not just time slices). We can hope to find new symmetries that correspond to different codimension 1 surfaces which aren’t time slices.

When we generalize this scenario, the unitary operators are generalized to “topological operators” and the rule U(t)=U(t’) is also generalized to arbitrary codimension 1 surfaces.

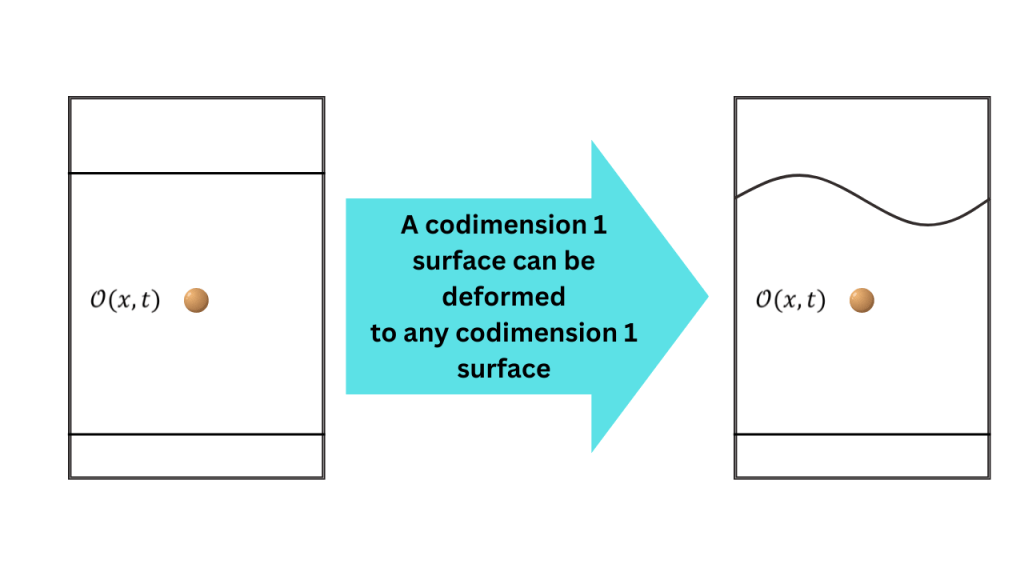

In the scenario with time slices, when we deformed U(t”), time slices were deformed to other time slices but now, we can deform a codimension 1 surface to any other codimension 1 surface.

Now, one can immediately see a possible generalization here. Why stop at codimension 1 surfaces? Why not talk about codimension m surfaces? A codimension m surface will have d-m dimensions. It turns out that we can do it and this is one of the ways how we generalize the concept of symmetries.

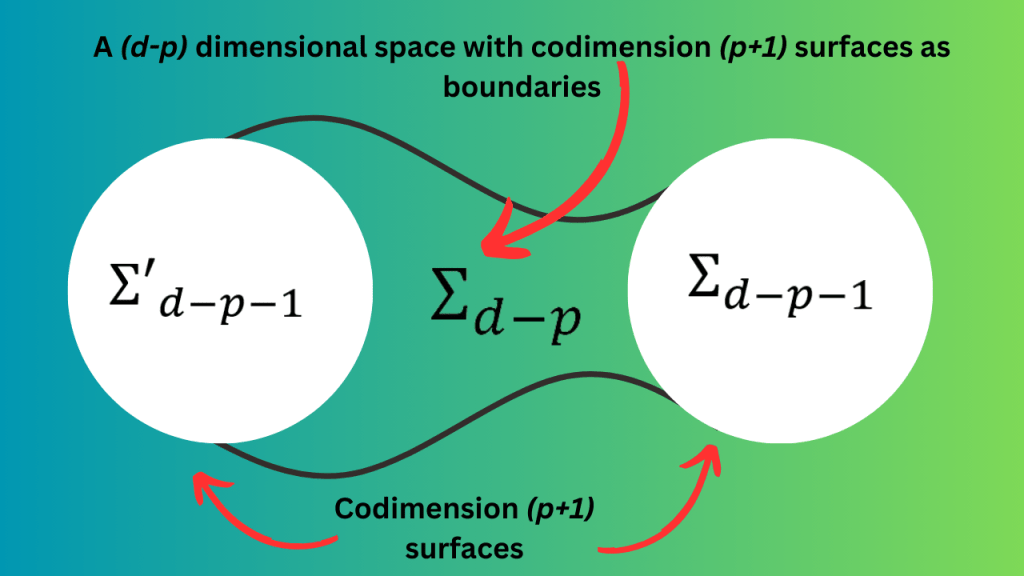

The symmetries that we talked about earlier are called 0-form symmetries. Their topological operators are associated with codimension 1 surfaces. The generalization of this scenario is to have p-form symmetries whose topological operators are associated with codimension (p+1) surfaces (their dimension is d-p-1). We can talk about (d-p) dimensional spaces that have these surfaces as boundaries.

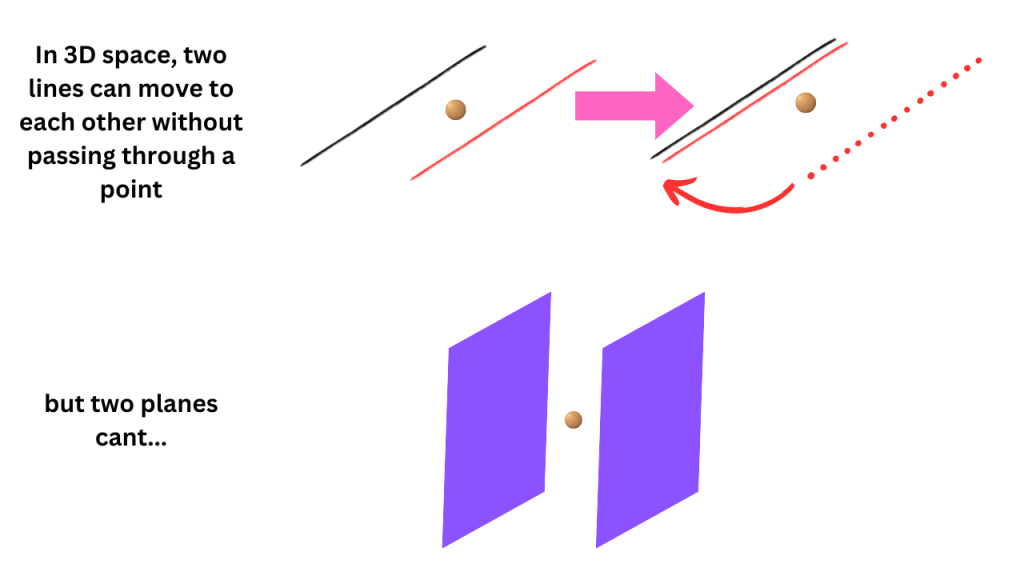

We can now try to define the action of codimension (p+1) topological operators on local operators. For this purpose, we put a local operator in the (d-p) dimensional space shown above. It turns out that there is no meaningful action of these operators on local operators for p>0. This is because we can make one topological operator meet the other one without ever having to go through the local operator.

As an analogy, take two lines in 3D space and we can see that we can make one line meet the other without going through a point between them. If we had two planes in 3D space, then going through a point between them is inevitable.

In 3D space, lines are codimension 2 surfaces, and planes are codimension 1 surfaces. So, we see that in this example, there is no meaningful action of codimension (p+1) operators on local operators for p>0.

Therefore, we can define the action of codimension (p+1) operators on higher dimensional operators instead of local operators (which have dimension 0). If these higher dimensional operators have dimension q, then it turns out that codimension (p+1) operators can have meaningful action on q dimensional operators only if q is not smaller than p.

The general symmetries that I have described above are called higher-form symmetries. In future posts, I will write more about them and about other generalized symmetries. I will end this post with a simple example of higher-form symmetries.

In electromagnetism in d dimensions, we have two higher-form symmetries. One of them is an electrical 1-form symmetry and the other one is a magnetic (d-3)-form symmetry. The operators on which these acts are called the Wilson line for the electrical symmetry and the ‘tHooft operator for the magnetic symmetry. Please note that for d=4, both of these symmetries become 1-form symmetries. (To be continued)

2 responses to “What are generalized symmetries?”

thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure

LikeLike