In this post, I will give arguments to motivate why Schrodinger equation has the form that it has. An understanding of classical mechanics, eigenvalues and eigenfunctions is required for following this post.

In conventional formulation of quantum mechanics, there are some postulates. Among them, three postulates are as follows.

- The state of a system is described by a function called the wavefunction.

- Observable quantites of a system are interpreted as Hermitian operators.

- The eigenvalues of an operator are the possible outcomes when the observable corresponding to that operator is measured.

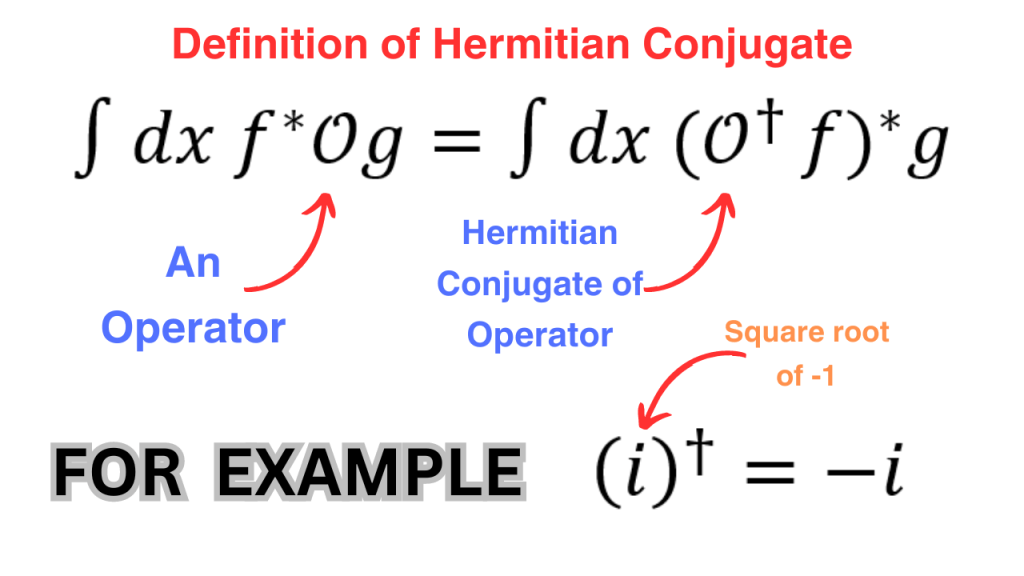

The “operators” mentioned above operate on functions. The term hermitian operator needs some explanation. Firstly, we define the “hermitian conjugate” (sometimes called just the “conjugate”) of an operator as follows (f and g are just functions).

A hermitian operator is an operator that equals its conjugate. The reason to interpret observable quantities as hermitian operators is a nice property of hermitian operators i.e. if we have a hermitian operator, then its eigenvalues are real. Since we want the outcomes of a measurement to be real, the eigenvalues of the observable operators should be real and hence, the operators should be hermitian.

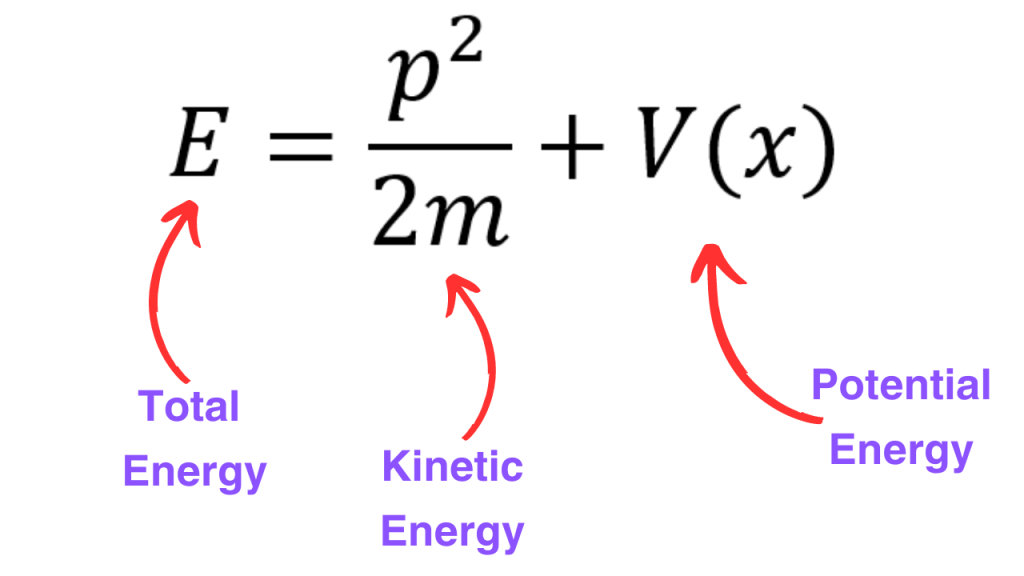

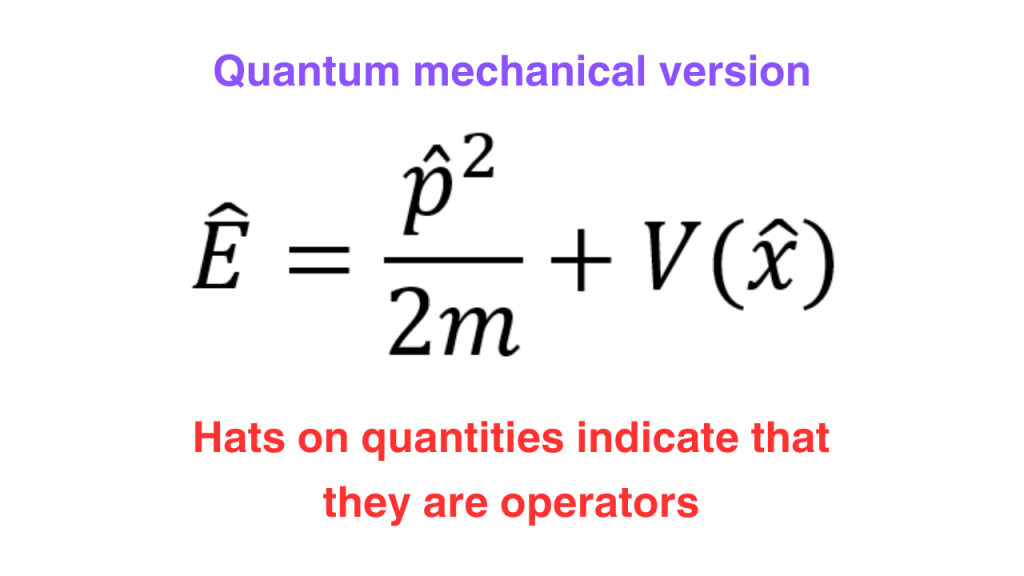

Now, in classical mechanics, we can write down the total energy of a system as a sum of kinetic energy and potential energy (there are some systems where we have other forms of energies but we aren’t talking about such systems).

In this equation, we have three different observales i.e. momentum, position and total energy. If we know the operators corresponding to these observables, then we would have found the quantum mechnaical version of this equation. We will see that this quantum mechanical version is the Schrodinger equation.

We will talk about the position observable first. The form of the operator of an observable depends on the “basis” in which we are writing down the form of the observable. For example, a vector can have different components, depending on the basis vectors we are using. The most popular basis for most applications in quantum mechanics is called the “position basis” and in this basis, position operator is just the position itself (i.e. position operator acts on a function by just multiplying the function with the coordinates).

Let me mention that there is more than one way to get the energy and momentum operators. I will provide a simple to follow way to deduce them.

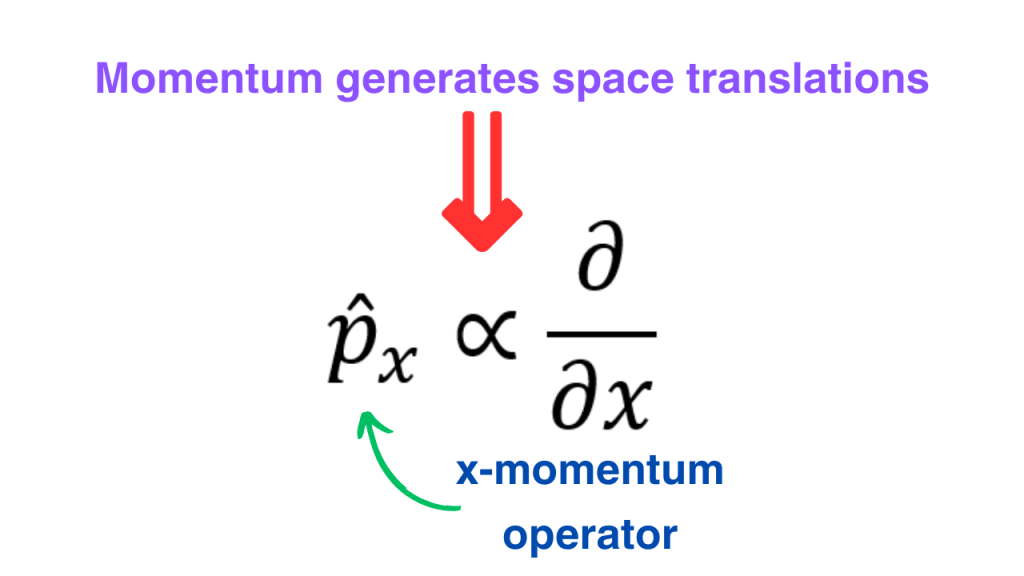

Let’s start with the momentum operator. From our understanding of classical mechanics, we know that momentum in x direction (also called the x-momentum) generates translations in x direction. It means that x-momentum should be proportional to the x-derivative.

The units of the momentum operator should be the same as the momentum. The x derivative has units of inverse length. We have to multiply it with some quantity that has units of energy multiplied by time. Such a quantity is the reduced Planck’s constant.

This proposed operator for x-momentum is still not hermitian. The conjugate of the x-derivative is the negative of x-derivative. So, we should multiply some number proportional to the imaginary number i to make the momentum operator hermitian. Let’s call this constant of proportionality “a”.

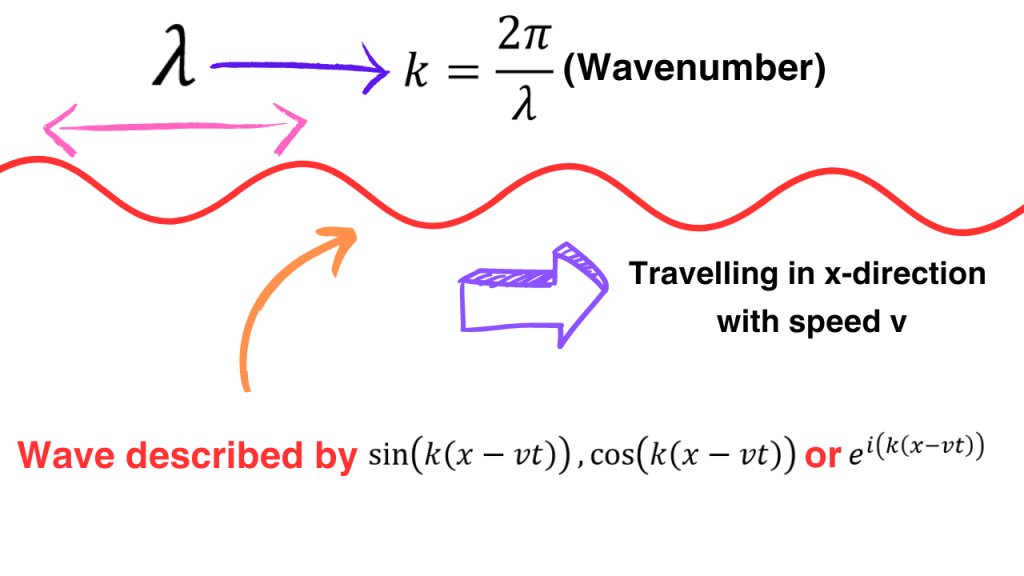

Now, let’s use some classical results about waves. We know from classical theory of waves that if a (plane) wave if travelling in x-direction, then the wave is described by the sine, cosine or complex exponential of k(x-vt) where k is the wavenumber and v is the speed of wave.

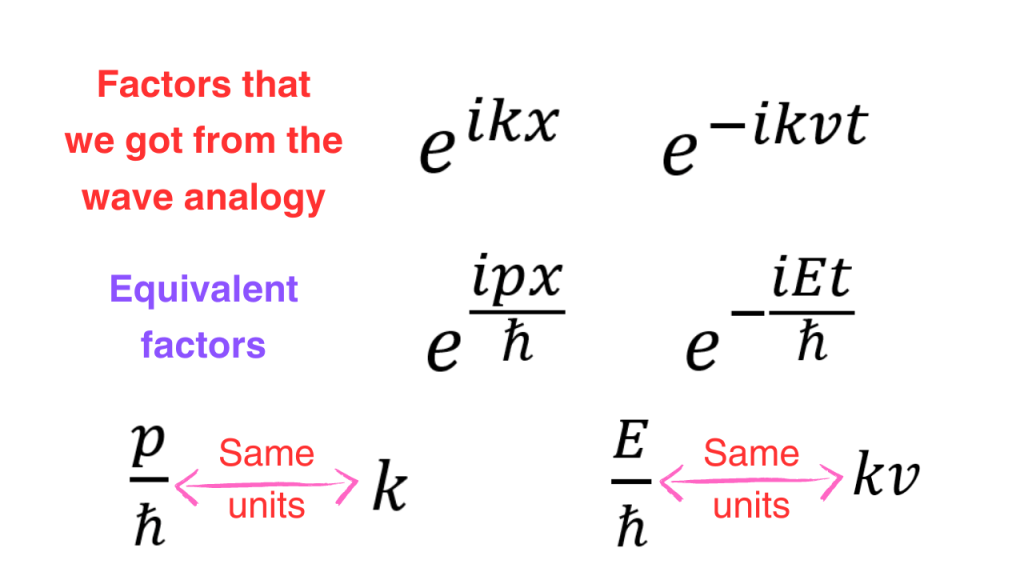

So we see that the exponential depending on x and exponential depending on t should have the following forms (here, E is energy and p is the momentum in x direction where I took out the subscript to avoid clutter).

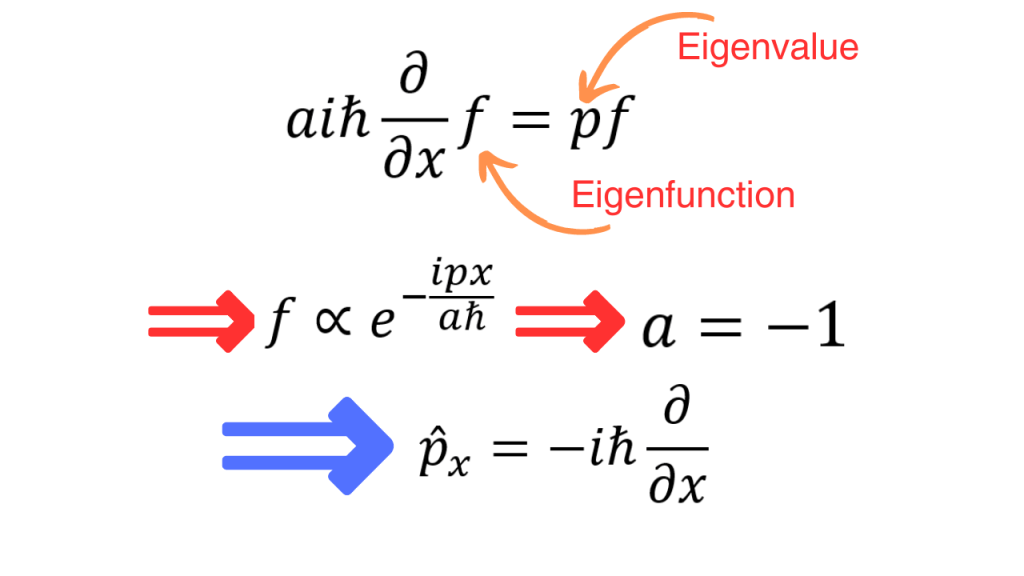

We can now take our proposed operator for the x-momentum operator and impose the fact that its eigenvalue is the momentum. If we try to find the corresponding eigenfunctions and compare them to the exponentials that we got from a classical wave, we see that a=-1. So, we have the final form of the x-momentum operator.

This expression for the x-momentum operator can be generalized to an expression for the three dimensional momentum operator as follows.

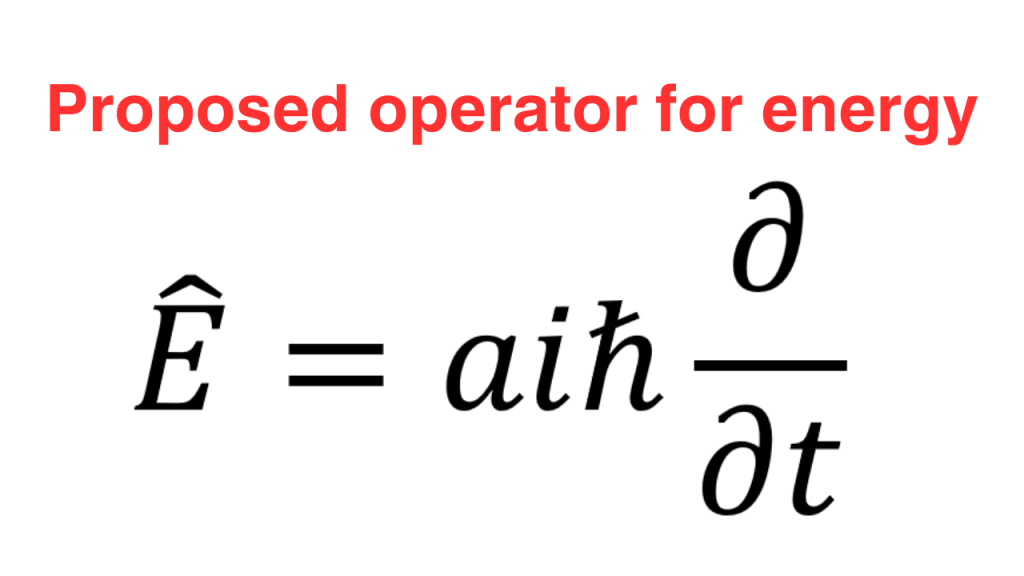

We can do the same procedure with the energy operator. We recall from classical mechanics that energy is the generator of time translations and hence, energy is to time like momentum is to space. Therefore, the form of the energy operator should be the same as the x-momentum operator with x replaced by time t and possibly a different value of the proportionality factor a.

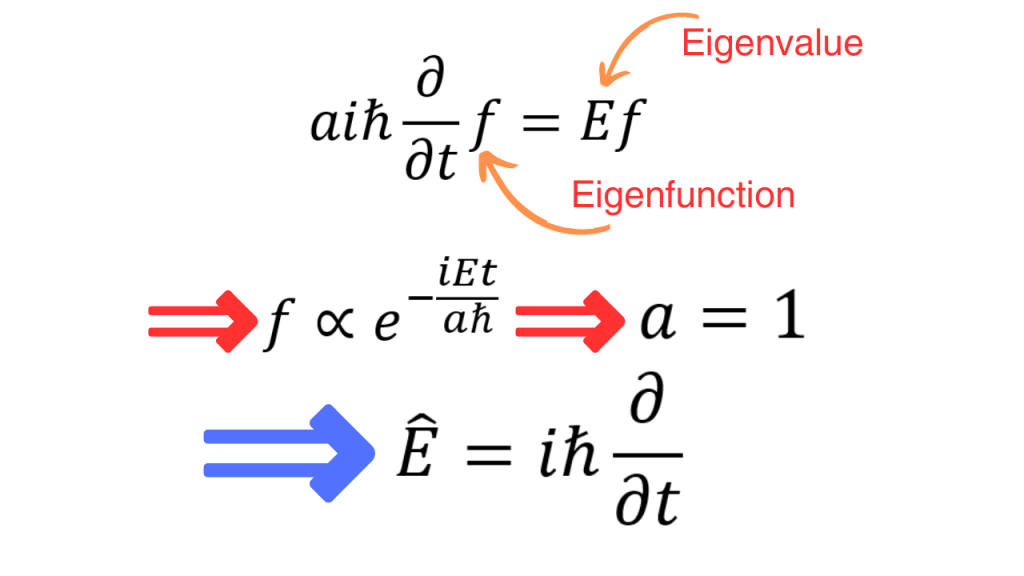

If we impose the fact that eigenvalue of the energy operator is energy (E), calculate the corresponding eigenfunctions and compare the result with the exponentials we got from the classical wave, we see that a=1. So, the final form of energy operator is as follows.

Now, if we use the energy and momentum operators, we can write down the quantum mechanical version of the expression for total energy. Since the quantum mechanical version has operators on both sides, they can act on a function. This function is nothing but the wavefunction. The one dimensional and three dimensional versions are written as follows.

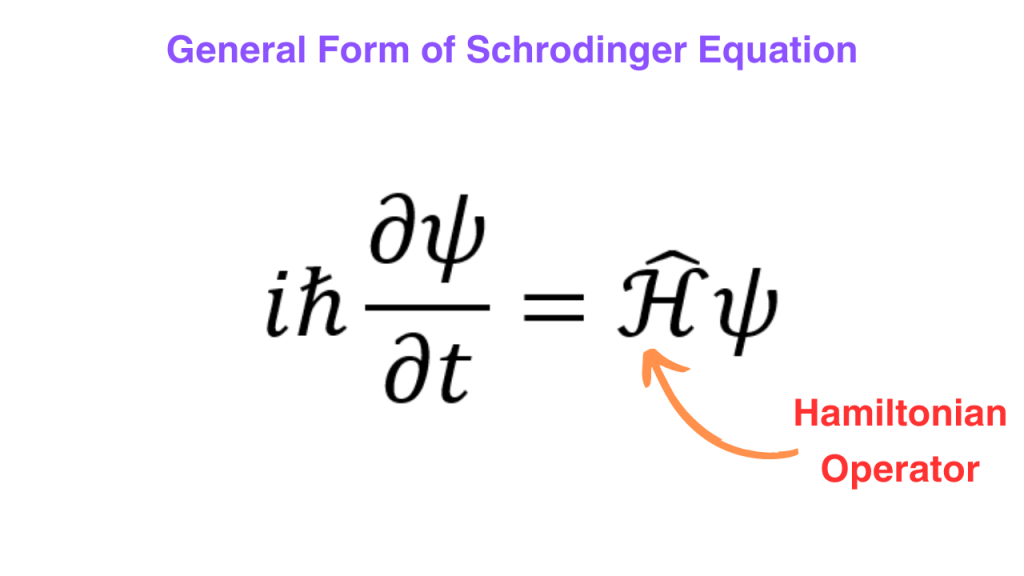

We have derived the non-relativistic Schrodinger equation. For a lot of systems, the total energy can be given as the sum of kinetic and potential energies but it is not true for all systems. For the general case, we can replace the right hand side of the equation that we got above by an operator called the “Hamiltonian” operator acting on the wavefunction.

The hamiltonian operator is also called the “energy” operator of a system and it tells you how the energy of a system depends on the degrees of freedom of the system. Therefore, the general form of the Schrodinger equation is given as follows.