This is a post that tries to answer the question, “How do we come to know that in string theory, there ‘can be’ extra dimensions in space?”. Some basic understanding of quantum field theory and general relativity is assumed as a prerequisite.

Firstly, I want to point out why I have written ‘can be’ instead of ‘are.’ This statement is closer to truth. We will see why that is the case later on (if you think I will only talk about compactifying extra dimensions, let me clarify that it is not the case).

There are multiple ways to answer this question. So much so, that the most comprehensive book on string theory (String Theory by Joseph Polchinski) proves in seven distinct ways that in string theory, there can be extra dimensions of space.

I won’t delve into a lot of mathematical details in this short post because it requires a substantial background. However, I will provide some details and try to clarify the reasoning that leads us to the conclusion that there can be extra dimensions.

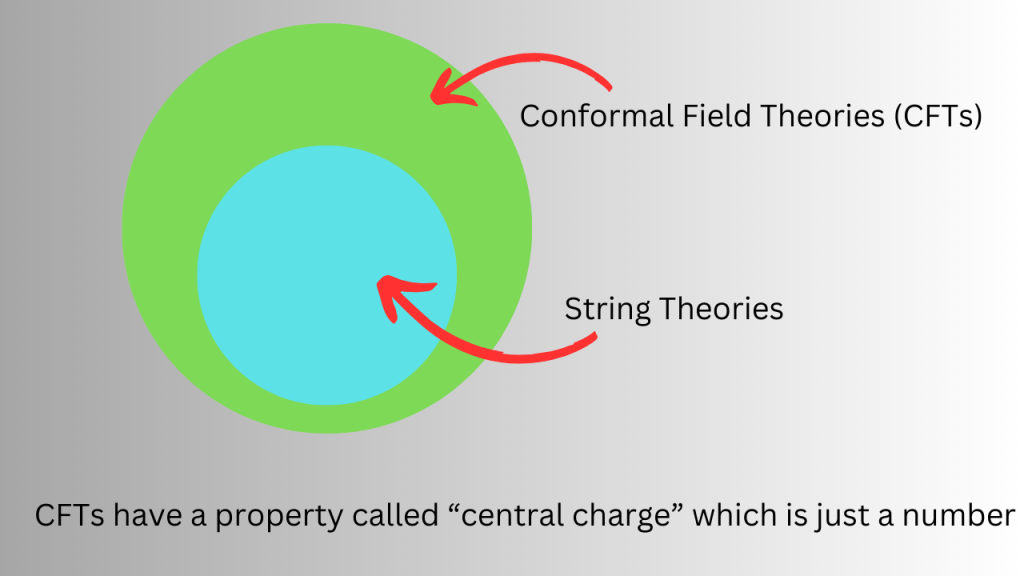

Firstly, string theory is a specific type of theory i.e. it falls in a particular class of theories. Theories in this particular class are called Conformal Field Theories (CFTs). Any CFT has a property known as the central charge (denoted as c). The central charge is just a number.

Now, if a string moves in any spacetime, it will also include those spacetimes that are curved. If a string moves in a curved spacetime, it is possible for the theory to be inconsistent.

It turns out that for the theory to be consistent, the expectation value of the trace of the stress-energy tensor should be zero. It turns out that this expectation value is proportional to the product of the central charge of the ‘entire theory’ and the Ricci scalar of the spacetime. This expectation value is called the Weyl anomaly.

If the spacetime is curved, it is possible that the Ricci scalar isn’t zero. Therefore, to make sure that the expectation value of the trace of the stress tensor vanishes, the central charge of the ‘entire theory’ should be zero.

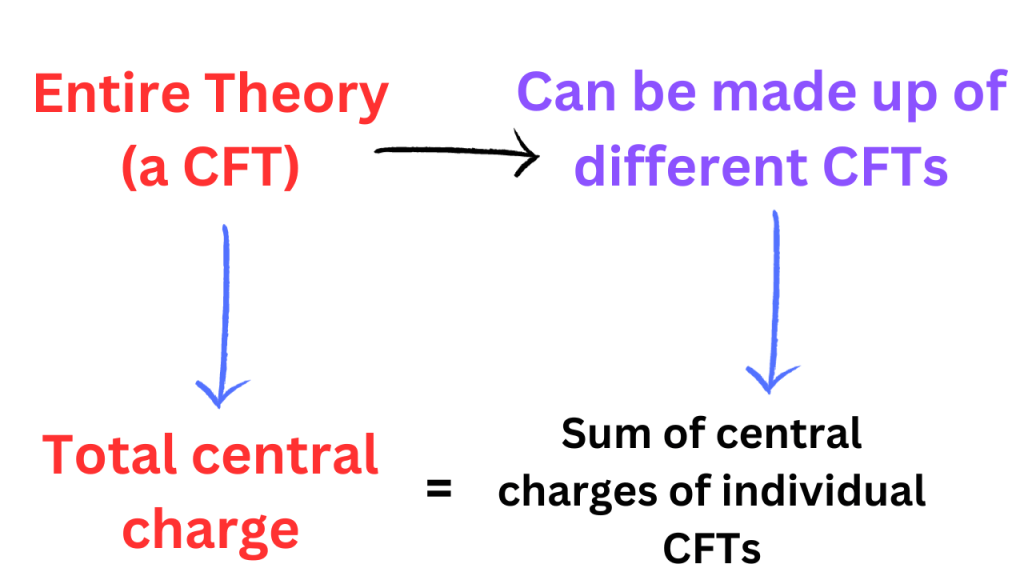

I used the term ‘entire theory’ above because the overall theory (which is itself a CFT) can be constructed by combining more than one CFT, and the central charge of this overall theory is a sum of the central charges of all those theories.

The upcoming details apply to both bosonic string and superstring theories, but I’ll keep it simple by talking about bosonic strings for some time.

When we write the fundamental equation of string theory, a problem arises. This problem doesn’t only exist in string theory but in more general types of quantum field theories called gauge theories.

In gauge theories, some field configurations are equivalent to other field configurations. Such field configurations are called gauge equivalent to each other. When we are integrating over all possible field configurations (e.g. in a Feynman path integral), we don’t want to count two equivalent field configurations. We want to count just one of them.

There is a procedure to avoid this overcounting called the Fadeev-Popov procedure (Fadeev and Popov are names of individuals). When we apply this procedure, some new fields enter our theory that weren’t present before. We call these new fields Fadeev-Popov ghosts.

Such ghosts also appear in string theory. There are two types of ghosts in bosonic string theory: the b ghost and the c ghost. The b and c ghosts together form a CFT known as the bc ghost system. When we calculate the central charge of the bc ghost system, it turns out to be equal to -26.

Since the central charge of the ‘entire theory’ should be zero, both the bc ghost system and the rest of string theory should have a central charge of zero. This implies that the central charge of the remaining string theory is exactly 26. This remaining string theory is called matter CFT and we will use this term from now. So, the true statement is that “the central charge of matter CFT (not dimensions) must be 26”.

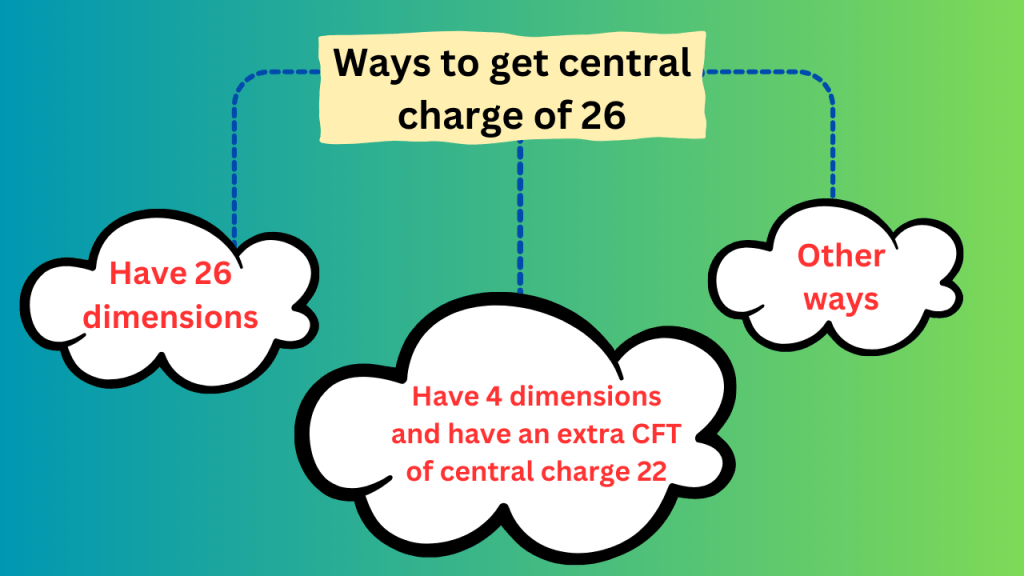

Now, there are several ways to achieve a central charge of 26. One way is to make the theory 26-dimensional. But this is not the only way. We can make the theory 4-dimensional and say that the rest of string theory is another CFT having a central charge of 22. It is essential that the sum of dimensions and the central charge of the remaining CFT is 26. If the theory is 26-dimensional, then there should be no additional CFTs.

The situation for superstring theory is similar but with a little modification. In addition to the bc ghost system, superstring theory has an additional ghost system called βγ ghost system. Its central charge is 11. Therefore, the total ghost central charge is -26+11=-15. So, central charge of the matter CFT should be 15.

In superstring theory, if we have d dimensions, their contribution to the central charge is 3d/2. Therefore, if we want the central charge to be 15, then d should be 10.

Therefore, superstring theory can have 10 dimensions but just like bosonic string theory, we can have 4 dimensions (which will give a central charge of 6) and fulfill the rest of the central charge (15-6=9) by some other CFT.