This post summarizes the main ideas behind supersymmetry. Pre-requisites to read this post include some familiarity with Poincare algebra and basics of quantum field theory (especially the basics of fermions)

In relativistic quantum field theory, we have a certain amount of spacetime symmetries. These symmetries include 3 rotational symmetries (along three space directions), 3 boost symmetries (along three space dimensions) and 4 translational symmetries (along four spacetime directions). These 10 symmetries are collectively called the Poincare symmetry. One can calculate the commutators of the generators of these symmetries and the collection of these commutators is called the Poincare algebra.

One can now ask the question, “Can we add more spacetime symmetries to the Poincare symmetries without introducing some serious problem?”. The answer to this question was given by Sidney Coleman and his student Jeffrey Mandula in 1967. The proved a theorem (now known as the Coleman-Mandula theorem) which says that, given some reasonable assumptions, you can’t add more symmetries to the Poincare algebra. These assumptions are as follows;

- For any given threshold mass, there is a finite number of particles that have a mass less than this threshold mass.

- Consider two particles in some state (a two-particle state). These particles are bound to go some reaction at almost all energies (almost all means all energies, except possibly an isolated set of energies).

- Consider two particles undergoing some elastic scattering. The amplitude of this scattering is an analytic function of the scattering angle for almost all energies and angles.

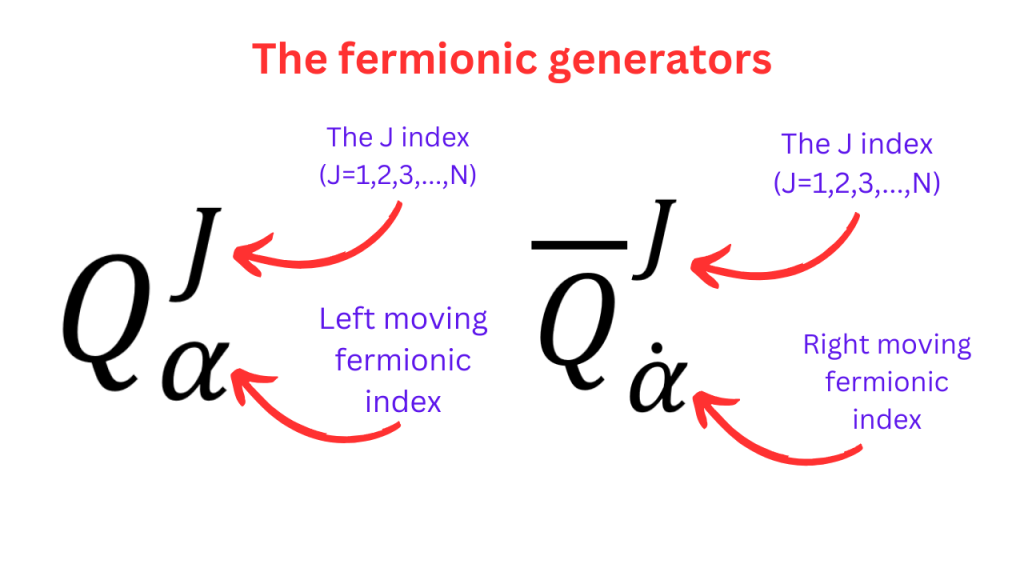

The Coleman-Mandula theorem seemed to close this chapter. Poincare symmetry seemed to be the only spacetime symmetry that you can have. However, in 1974, Julius Wess and Bruno Zumino came up with certain field theories that had symmetries whose generators were a bit different from the generators of the Poincare symmetry. In contrast to the Poincare generators (that only carry Lorentz indices), these new generators carried a fermionic index as well. It means that these generators behave like a fermion under Poincare transformations. There generators could be further subdivided into the left moving and right moving fermionic generators. The right moving fermionic generators are identified by placing a bar over the generator and a dot over their fermionic index. You can add more than one such fermionic generator. In this scenario, we add an index (called J which can take values 1,2,3,…,N) to label different such generators. This new kind of symmetry is called “supersymmetry”.

The Coleman-Mandula theorem hadn’t taken the possibility of fermionic generators into account and thus, Wess and Zumino were able to bypass the Coleman-Mandula theorem. In 1975, inspired by the triumph of Wess and Zumino, three physicists (Rudolf Haag, Jan Lopuszanski and Marin Sohnius) were able to show that if one takes the assumptions of Coleman-Mandula theorem and allows for the possibility of fermionic generators, then the only additional generators for spacetime symmetries are the generators that Wess and Zumino considered. These generators carry one fermionic index and commute with spacetime translations. In addition to the Poincare algebra, the following commutators and anticommutators make up what is called the “supersymmetry algebra” (also called the SUSY algebra).

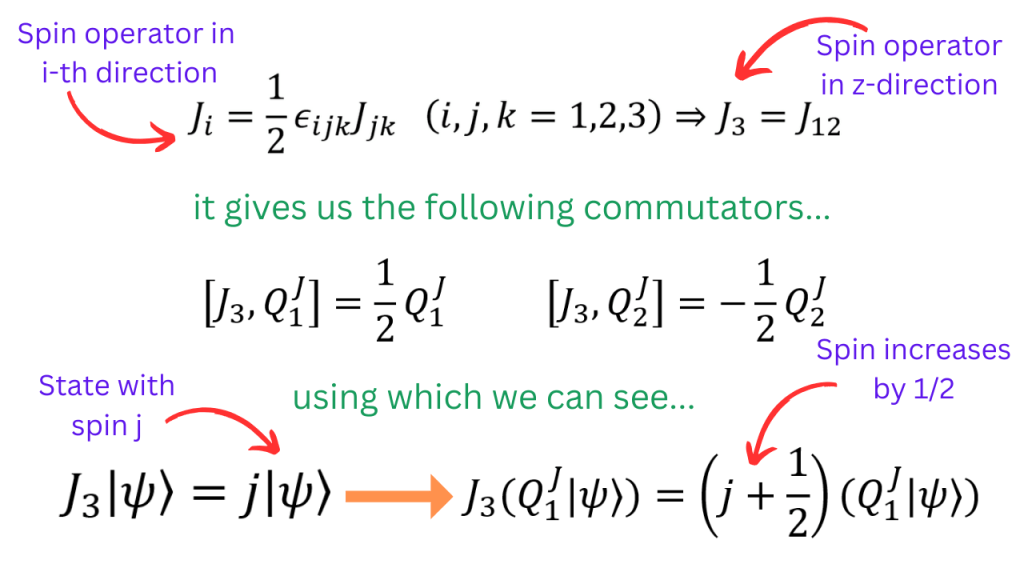

Supersymmetry generators change the spin of a state. A single supersymmetry generator changes the spin of the state by 1/2. This can be seen as follows (using the SUSY algebra);

Now, we can start with some vacuum that has spin j (such a vacuum is called the Clifford vacuum), we can act on it by one or several SUSY generators. This action creates new states that have different spins than the original spin (each additonal SUSY generator increases the spin by 1/2). If we add just one fermionic generator (which means that the index J can only take value 1) then we don’t need to add the index J and this supersymmetry is called N=1 supersymmetry. In this scenario, we just have two states (i.e. the Clifford vacuum with spin j and one additonal state with spin j+1/2).

This shows that if j is an integer (which means that the Clifford vacuum is a bosonic state) then the other state (of spin j+1/2) should have a half integer spin (which means that this state is fermionic). Similarly, a half integer j will result in j+1/2 being an integer. Therefore, the N=1 supersymmetric introduces a fermionic state for a bosonic state and vice versa.

Since we have additional fermionic states in supersymmetric theories, we will have additional terms when writing down the Feynman diagrams. We will have fermionic loops in addition to the already present bosonic loops. A reader familiar with fermionic QFTs will recall that in fermionic loops, one usually gets an overall minus sign. This additional minus sign is very important in supersymmetric theories because this causes the fermionic loops to cancel the bosonic loops.

This attribute of supersymmetry causes the higher loops corrections to vanish. This fact culminates in “Non-renormalization theorems” about supersymmetric theories. In theories with four fermionic generators (i.e. when J can be 1, 2, 3 or 4), which are also called N=4 supersymmetric theories, all the loop corrections go away. The absence of higher loop corrections in supersymmetric theories was one of the motivations to pursue these theories. It was thought that SUSY theories can explain why the mass of the Higgs boson doesn’t get higher loop corrections (if it did, then the mass of the Higgs boson would be close to the Planck mass, which it isn’t).

With this post, we have barely scratched the surface of the attributes of supersymmetry. Supersymmetry is a very vast field with different dualities (e.g. Seiberg Witten duality, Olive Montonen duality and Gaiotto dualities) and it also gives us toy models to understand the solution methods of even the hardest problems (e.g. the problem of quark confinement has been solved in supersymmetric version of quantum chromodynamics, called SQCD). One can read this and specially this review to read more about supersymmetry.