In this post, I will try to explain why all three laws of motion are independent and why the first and third laws of motion aren’t special cases of the second law.

Newton’s first law of motion says that “An object continues its state of motion until an external force is applied on it”. However, this statement is true in inertial frames only. In fact, this law is also the definition of inertial frames. People have come up with other (ad-hoc) definitions of inertial frames (e.g. a frame which has zero acceleration with respect to distant stars) but Newton’s first law is THE (non-adhoc) definition of inertial frames. First law declares the existence of special frames where the laws of motion take very simple form. Why should such frames even exist? The answer to this question isn’t very well-understood. The fact that such frames exist is a nontrivial fact and the first law assumes their existence.

The second law says that the acceleration (a) experienced by an object of mass m due to a force (F) is equal to F/m. In an alternative, more well-known form, we have F=ma. Now, this equation is only true in inertial frames. Tt is easy to see this fact that by putting F=0 (no external force), which implies a=0 (state of motion doesn’t change), assuming that mass isn’t zero.

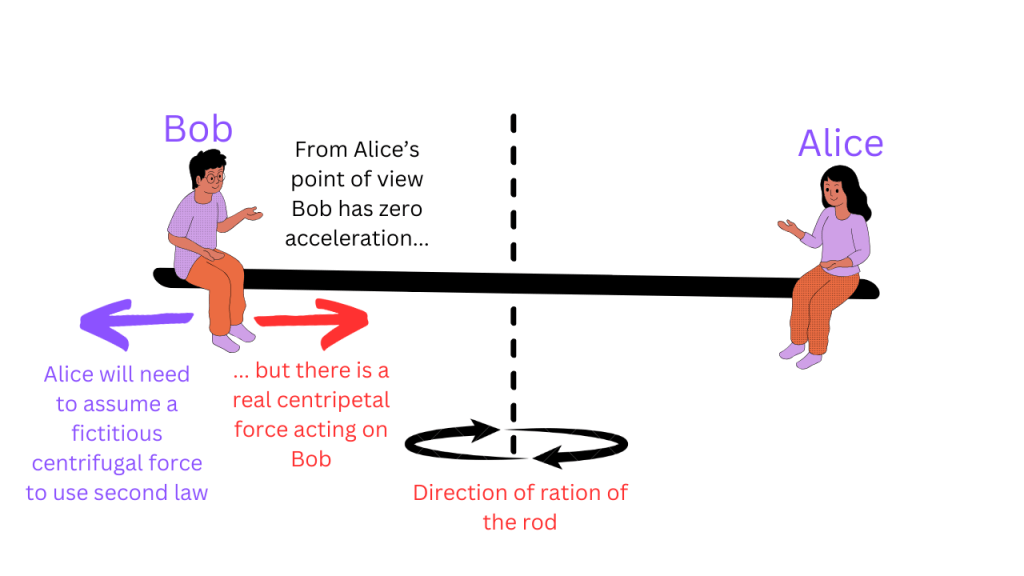

In non inertial frames, one can use the second law only if one comes up with fictitious forces (also called phantom forces or non-Newtonian forces). An example of such a force is centrifugal force. Imagine a rod rotating about its axis of symmetry and an observer at each (called Alice and Bob). From the point of view of Alice, Bob doesn’t move (i.e. has zero acceleration) but there is a centripetal force acting on Bob (which is a real force). Alice’s observation of Bob’s motion is inconsistent with Newton’s second law (which isn’t surprising because Alice is a non-inertial observer).

However, Alice can make her observations consistent with second law of motion if she assumes that there is an additional force that is equal in size but opposite in direction to centripetal force, called the centrifugal force.

However, you can see that this procedure requires invoking imaginary forces and thus, Newton’s second law isn’t true in non-inertial frames. However, this fact isn’t derivable from the second law itself and thus, the first law isn’t a special case of the second law.

What about Newton’s third law? Let’s talk about it. There are actually two versions of the third law, called the weak version and the strong version. The weak version says that “If particle A applies a force (called F) on particle B, then particle B applies a force on particle A which is equal in size but opposite in direction (i.e. -F)”. However, the strong version of the third law also says that the forces F and -F lie along the line that connects particle A and B.

All the known forces obey the strong version except the magnetic force. Imagine a moving charged particle, which creates a magnetic field of its own. Under the influence of this magnetic field, another moving particle will experience a magnetic force. However, this force isn’t along the line that connects these two particles.

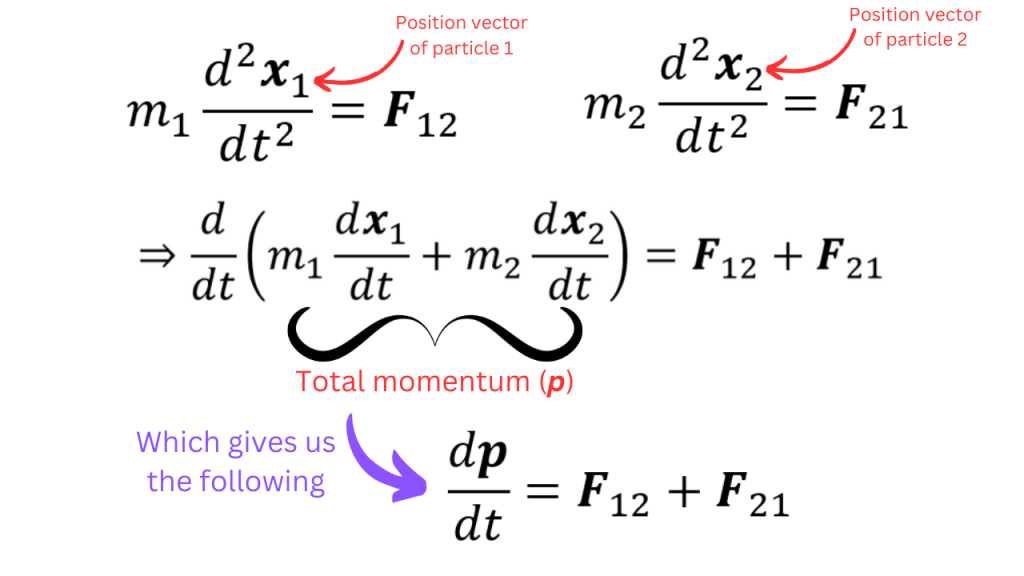

Now, an argument an be given that tries to establish that the third law is a special case of second law. Consider two particles (particle 1 and 2). There is no force that is applied to these particles except the forces that they apply on each other. Let’s denote the force that particle 1 applies on particle 2 as F12 (this is a force vector) and the force that the particle 2 applies on particle 1 as F21 (this is a force vector too). Now, the second law can only give you the following equations.

Now the argument says that since there is no external force on this system of two particles, the total momentum of the system should be conserved and thus F12+F21=0. However, this argument is circular as I will explain shortly. It assumes the conservation of momentum for a system of two particles, none of whom is a free particle. From second law, you can show that a particle will have constant momentum if it is free (i.e. no force acting on it). This result will extend to a set of N free particles. However, if the particles in a system of N particles are exerting forces on each other, the conservation of momentum of the whole system doesn’t follow from the conservation of momentum of a single free particle.

The law of conservation of momentum for a system of N particles says that “If there is no external force acting on the system of N particles, then the total momentum of the system (i.e. the sum of the momenta of all particles) is conserved”. The thing to understand is that to derive this law of conservation of momentum, you need to assume the third law of motion. For the derivation, see section 1.2 of Classical Mechanics by Goldstein, Poole and Safko (Third edition). Therefore, you can’t argue that the third law is a special case of the second law using the conservation of momentum when you can’t derive the law of conservation of momentum without using the (weak version of) third law in the first place. Therefore, the argument presented above is circular. Although this is besides the point, but let me just state that to derive the law of the conservation of angular momentum, you need to use the strong version of the third law.

One can say that you could have used the fact that for the system described above, we could have used the fact that the momentum of the center of mass of these two particles should be conserved. If you calculate the time derivative of the momentum of the center of mass, it is also proportional to F12+F21. Since the time derivative is zero, it implies F12+F21=0 which implies that the two forces are equal in size and opposite to each other. However, the fact that for a system with no external forces, the momentum of the center of mass is conserved is itself derived from the law of conservation of momentum. Therefore, you can’t use this principle either to argue that the third law is a special case of the second law.